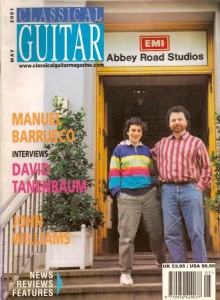

David Tanenbaum Interview

by Manuel Barrueco

Originally appeared in Classical Guitar Magazine (England), May 2001. Reprinted with permission.

Manuel Barrueco: I was thinking back about our history together and all the work that you have done with contemporary music….I thought it would be fun to do an interview together and reminisce.

David Tanenbaum: I’ll tell you something about our history that I remember. We used to have races with the VillaLobos Etudes. We would start: one, two, three, GO!

MB: I don’t remember that, but I do remember the first time I heard you. It was in a repertory class at Peabody when we were both students there. I walked in late (if my students only knew what a bad student their strict teacher was! ) and you were playing a piece from the Joffrey Ballet’s ‘Viva Vivaldi’, and I just remember how awful it was…

DT: OK, end of interview…

MB: No, kidding aside, I do remember being impressed by how beautiful it was. I thought the piece was so pretty. It was part of the ballet, but it wasn’t really Vivaldi, was it?

DT: It was the first movement, which was composed in the style of Vivaldi. The ballet used a three movement Vivaldi violin concerto that works pretty well on guitar, and the solo piece was played before the three movements.

MB: Had you played that professionally?

DT: I had. From my last year in high school I toured it around the US. And during my first semester at Peabody we went to the Soviet Union.

MB: I feel touring something like that is hard. I don’t know how it is to tour with a ballet, but I imagine that it’s a whole different game – that you can’t skip a beat.

DT: There is some flexibility but you have to be rhythmically there. The challenge is to find something new in the piece all the time, to keep it fresh. And I got into the dancers. I would go into the wings a lot and watch them work.

MB: When I’ve toured a concerto, I find that it gets more difficult as the tour goes on. Every day it gets harder and harder to find the energy and concentration to do it.

DT: Exactly. I just have done two sets of four and I find the same thing. You do it the first night and then there can be a sense of let down. I find it easier to get on stage but more difficult to keep the energy high.

MB: And the concentration, right? It’s easier for the mind to wander.

DT: It does, and you know, the different acoustics can throw you. If you are in a different hall every night it’s a new adjustment.

MB: You got the Joffrey tours from Rolando Valdes-Blain. He was your teacher, right?

DT: Rolando was my teacher for about 4 years. You know him; he was dealing art and doing other things and he would have only two or three guitar students at a time. My lessons began every Saturday in Greenwich Village at 1 o’clock and he would just be waking up. He would get a cigar and a bottle of wine and sit on his couch and the lessons went on until 5 or longer. We just played all afternoon.

MB: I remember you saying that he was a very generous man.

DT: Yes. He didn’t have a systematic way of teaching but he did teach me how to think on the instrument, how to finger, how to conceive things on the finger board. And he cared a lot. He spent endless amounts of time and charged very little.

MB: So what do you remember about your years at Peabody?

DT: I remember Michael Hedges being a very average, sort of dull student, showing no signs of what he would later do. And I remember you and I feeling that we were rebels. We were together one year at Peabody, your last year was my first. Now at Peabody there are several people doing different things on the faculty but back then there was only one way to do things. And I would say that we fit into it “more or less”.

MB: The thing about Peabody right now is that even though Ray Chester, Julian Gray and myself in some ways are different we all came from Peabody so there is some common ground, and we certainly understand each other. I think that is positive.

DT: But in terms of teaching you’re probably very different, right?

MB: It depends on the perspective. From a certain perspective I’m sure that it may all look very similar, but from the inside it can look different.

DT: When I was forming the guitar department in San Francisco I wanted people that had different interests and approaches, and who came from different backgrounds.

MB: So one day you came to me and asked me if I wanted a job teaching at the Manhattan School of Music.

DT: Pretty nice guy, huh? Yes, my father was teaching there for years and Dean Simon came to me and said “Who should I hire?” I chose you and recommended Rolando as well.

MB: Yes, you know students often ask me “how do I get a job teaching?” and I tell them that I’m the wrong guy to ask. I don’t know really. I was offered a job before graduating.

DT: It was such a different time, with so few people around.

MB: I thanked you then, and I thank you again.

DT: Make sure you write that.

MB: I will.

DT: It’s an interesting idea to go to a freshman at college and ask him to form a guitar department.

MB: I have to say also that for me it was kind of difficult. I went to Manhattan School of Music and I think I was maybe 22 years old with no experience and with a lot of the students being older than I was. I often didn’t know what I was doing. I remember at that time trying to be very open minded, to let the students do their own thing. And I remember having a conversation with Dean Simon about that, saying “Well I’m trying not to influence the students too much” and he said: ‘OK, ok, that all sounds very good, but you HAVE to influence them, you have to tell them what you think because it’s the only thing you know.” That was a turning point for me because I realized that when I was a student the teachers that had the greatest impact on me, and I am not necessarily referring to guitar teachers, were the ones that would go out on a limb to tell us what they thought and made a strong point. Then it was up to us to react to it.

DT: I remember playing in an artistic retreat for the California State University system a few years ago. All the artists said they found their direction because a strong teacher influenced them, sometimes directly and sometimes because they rebelled against the teacher.

MB: Actually, I think I’ve become a better teacher since learning to just say what I think. And being able to say “I don’t know that.”

DT: Well, I think that’s a sign of being a mature teacher. When I was younger I would let the students just do what they wanted more. For instance, in terms of levels of repertoire, I would let people play things that were too hard for them. I think it’s a sign of a maturity to say “you can’t do that now”. Now I exercise way more control of repertoire and things.

MB: Yes, that would constitute bad teaching. All it does is let the student get into bad habits, get frustrated and get used to playing things badly.

DT: Teaching is a big responsibility. The truth is that you know a lot more than they do and they’ve given you their trust and you have to lay some lines down.

MB: Another thing that was important to at the time was when Stanley Bednard, who was the head of the string department, advised me that as a player I should always teach. And I’ve found that has been a great thing for me.

DT: I love the balance between the two. It makes me articulate my understandings more than anything else. And it tells you what you know: if you can’t say it clearly, you don’t understand it so clearly.

MB: I know that for me it keeps me pure…

DT: Pure?

MB: Yes in the sense that it makes me keep trying. There have been points in my life when I found myself kind of sitting back, sort of like “Ok that’s it, I’m doing it- I can just rest on it for a little while” and then you teach and you realize you can’t. It’s a challenge. Especially if I have to play the same repertoire my students are playing and they are playing it well, it really pushes me to keep trying my best.

DT: I sometimes look for shortcuts, but teaching students makes me realize that there just aren’t any shortcuts, you have to go through the whole process every time with every piece to get to the point of understanding.

MB: I saw you a couple of weeks ago in San Francisco, and one thing that I’m extremely impressed with is all the work you have done with contemporary music. Not only that I can’t think of a contemporary piece that you haven’t played, but also all the composers that you have worked with.

DT: Let me tell you how all that got started. When I was crawling around the living room, my father – who makes his feelings very clearly felt to everybody around him – was playing Stockhausen and other crazy things on big loud speakers. I was just a little kid getting blasted with this stuff, and I think I’ve just never been scared of that music since that age. I studied first piano and cello, and when I got to the guitar I remember my father coming by and saying: “You gave up Chopin and Lizst for Sor and Giuliani? Who are these guys? This repertoire stinks.” So I finally said: “Why don’t you just shut up and write me something?.” And so he did and I had this piece that was all mine. I got to explore it, I was the first one to play it, and I loved that so much that basically every time I met a composer I just said: “Why don’t you just shut up and write me something?”

MB: Your father is a composer and a teacher at Manhattan School of Music and Aaron Kernis (whom you have worked with a lot) studied with your father there, right?

DT: Aaron and I met in 1978 at the San Francisco Conservatory and then he

went to Manhattan School of Music and studied with my father. I think my father’s influence on him was pretty strong; I think my father freed something in him. And it was when he was studying with my father that he began the ‘Partita’ in 1981. We’ve been friends since then.

MB: So was your father influential in you getting to know some of these people? For example Steve Reich, how did you get to know him and work with him?

DT: Well, it’s interesting that you ask that because I can’t think of one composer that my father started me off with. I have an old friend from high school who played percussion in Steve’s ensemble. After Pat Metheny recorded Electric Counterpoint Steve was looking for a guitar player and my friend connected us. I toured the piece for two years with Steve Reich and Musicians. He’s like a rock star in Europe. It was like preaching to the converted – you walked on stage and they already loved you before you played.

The scariest moment was early on, during a concert in Stuttgart, when the tape just stopped in the middle of the first movement. I wasn’t really sure what to do but I thought that it might come back so I just kept the beat very steady and I played by myself for about 15-20 seconds. When the tape came back I was luckily exactly with it.

MB: I came to see you in one of those concerts in Cologne, Germany. Anyway, how did Electric Counterpoint come to be named Acoustic Counterpoint?

DT: That was done by my record company after I recorded it.

MB: So what’s the story about Nagoya Guitars?

DT: I got a call from Aaron Kernis one morning and he said: “I heard a piece in New York last night that I think is a two guitar piece.” So it was entirely his idea. He had heard “Nagoya Marimbas’, which is the original version. I called Steve (Reich) and he said: “People have been trying to transcribe this piece for all kinds of instruments, but I don’t think it’s going to work.” It’s actually sight readable in the original key, so I sent a tape to Steve and he rejected it. Then I changed the key, added some harmonics and generally made it more guitar-like, and now he loves it.

MB: I’ve come to the conclusion that probably as much, if not more than any other country in the world the US is the place right now for new guitar music.

DT: It very well may be. It’s happening everywhere. There’s a small army of us going out and getting all the composers to write for the guitar. I think the greatest composer now who has not written for the guitar is Ligeti. I have approached him and I know Starobin has approached him and he always says that he’s too old to learn a new instrument. I know that you are currently working with Arvo P’rt and one has to give a lot of credit to David Starobin for getting Eliot Carter to write for the guitar.

MB: It seems to me that there is a core of players of our generation here in the USA that have kept their focus on composers that are mainstream composers, and not only guitar composers. And it seems to me that here more than in other places (and this could be simply because of the size of the country) just more things are happening. So, what other American composers have you worked with?

DT: I’ve done a lot of work with Terry Riley, he’s writing me a series of 26 guitar pieces. We just made a cd and I think it could end up being three cds at least. He’s just going nuts with the guitar. What’s particularly interesting about that project is all the combinations he’s writing for. He’s got five pieces for flute that can be done with violin, two with percussion, a new one for guitar, viola and bass, and there is one for 3 guitars, percussion, violin and piano. So, it’s a really long project that started with a lot of bugging on my part and is starting to turn into something.

I’ve worked with Lou Harrison. He hasn’t written me anything directly but I’ve played his guitar pieces and arranged and published a lot of his other pieces. I’d love to get another piece from him. I think his guitar pieces are beautiful.

I’ve also been working recently with John Adams, who lives less than a mile from me. He has used the guitar in five of his most recent pieces, if I’m counting right. He used the guitar prominently in the second movement of his Naive and Sentimental Music, a 50 minute orchestral work that I just recorded with the L.A. Phil and Esa Pekka Salonen. And I had to do it on a steel string guitar. How much steel string guitar have you played?

MB: Not much, doesn’t that destroy your nails?

DT: It was really tough on them. I had maybe played steel string guitar for about 5-10 minutes in my life.

MB: Can you play with nails on it?

DT: I put all sorts of stuff on to harden them and it was okay for the weekend of recording. It was sort of a crisis because I played for Adams two or three days before the recording and he said “Well, beautiful playing but wrong instrument.” So I had to borrow a steel string guitar and learn how to deal with it. It was hard.

MB: One of the reasons why I wanted to talk to you about all this is that I think that you don’t get enough credit for all you’ve done. There are people who have done a fraction of what you’ve done and they are getting all kinds of recognition. You are not someone that goes out blowing you horn and bragging about all this stuff.

DT: Yes, I know. But the truth is that what really interests me is the musical part. That’s where my focus is, that’s were I want to be.

MB: That’s something that I love about the work that you have done, that it is about that. It’s very pure – I hate giving you compliments – [laugh] but it’s very much focused on the music and I really can’t think of anyone that puts more love into it.

One of the biggest influences I ever had in my life, somebody who opened a lot of doors for me, was Toru Takemitsu. I still remember the day in New York that you played ‘Folios’ for me and I thought at that moment, that it was the most beautiful music I had ever heard. This was in the late 70s, way before the whole Takemitsu wave.

DT: Yes, ‘Folios’ was written in 1974 and I think the only Westerners into that piece in the early days were Michael Lorimer and me. I felt like a missionary, I played it for everybody like I went to you. I remember going up to Bream after a concert and I said: “Great concert Maestro Bream, do you know Takemitsu’s ‘Folios’? You should play that piece!” He just looked at me like “who’s this kid?”

MB: Did he say whether he knew it or not?

DT: He said: “I know the piece and I’m actually carrying it around in my suitcase on tour”. I think he never ended up playing that piece but of course he ended up loving Takemitsu. The kind of relationship that you and I both had with Takemitsu is one of the most meaningful things to me, to work with a masterly musician like that.

I don’t know how you feel, but I think you can learn from anybody. Any guitar player that has spent a lifetime working at this instrument you can learn from, and I’ve learned a lot from students as well. But my most profound teachers are these composers like Takemitsu. His ears revealed worlds of sound to me, and some of those experience were unforgettable.

MB: When we were talking about him a couple of weeks ago, you said how he could get under your skin. He did that with me. I loved not only the music, but the person as well. I was so surprised to see how much it affected me when he died. I knew I would be affected but to this day when I think about it, it makes me choke a little.

DT: Me too. I knew he was ill and on the verge of going, but I tell you honestly, four years later the world still doesn’t seem the same without him in it. There are people in your life who have great power, and sometimes you don’t realize the extent of it until they go. I had a grandmother like that.

MB: We did the last orchestral piece he wrote, “Spectral Canticle” for violin, guitar and orchestra, and for me it is almost unfinished in the sense that he never got to hear it. I feel sadness about that. We never talked about it, he never heard it.

DT: His widow told me that he also didn’t hear “In the Woods” or the last flute piece.

MB: You had a certain quality when you played ‘Folios’. When other people played it, it sounded angular, but when you played it, it sounded like a folk song. You also had that kind of quality when you were doing the “Royal Winter Music.” I remember you playing it for me and I couldn’t believe how beautiful this piece was. So, I wasn’t a bit surprised when Henze decided to write a concerto for you.

DT: That’s very nice. Here’s my Henze story: I don’t know if you remember a pianist at Peabody called Carlos Turriago? He was a fine musician who knew a lot of contemporary music, and part of my great education at Peabody was hanging out with him and listening to his record collection. We used to stay up all night listening to new contemporary records that came out. And one of them was “El Cimarron”. That knocked my socks off. I could not believe what he came up with, and I always wanted to do that piece. I was out in San Francisco in 1980 when the phone rang offering a tour of the first English language production, and I jumped on it. Andrew Porter, the New Yorker critic, heard one of the performances and he told Henze about me. So when “Royal Winter Music” came out I was working on it right away, and when the Second Sonata came out I wanted to make a recording of the whole cycle. But there were so many differences between Bream’s recording and the score that I was just dying to play for Henze, to get some ideas, but mostly to get the score corrected. So I hung around this festival in California for a week listening to his music and waiting for a chance to play for him. Finally on Sunday morning, the last day of the festival, he called. He was in his bathrobe, drinking coffee and waking up. We went out on the porch and I started playing for him, and after the second movement he said: “I’m writing you a concerto.” It was such a shock, I almost started to shake. I had just wanted to get the corrected notes and to play for him. Finishing the last seven movements was hard after that.

You know, Henze is an extremely generous man. He didn’t need to write me that concerto, and he also could have said that and not followed it through, but sure enough he did. He found the commission himself, and three years later he did it.

MB: I remember you telling me that in a certain place in the score, there were a bunch of notes and that he just asked you to make a chord out of them.

DT: It surprised me because here is a guy who has written hours of guitar music, including one of the longest guitar pieces for solo guitar, and he’s writing chords that have 10 notes in them. He told me, ‘Look, these are all the notes I like, and you just pare it down and make the chord you want.’ So for instance, in the last movement of the concerto, ” An Eine A’lsharfe’, a lot of the chords are my voicings. And sometimes he would describe in words the sounds he wanted and then just ask me to come up with some way to do it, as in the last chord of the piece. So he wanted a very active participation, which was great for me.

MB: For me, with Henze, there is never a note that I wish was a different one.

DT: Yes, he is so incredibly expressive. Something like ‘Royal Winter Music’ just makes the guitar a bigger instrument that it was before. It’s just rings with expression. And I think “Drei Tentos” are as beautiful a little set of pieces as we have. If you made me choose what I think is the most beautiful guitar piece, they would be high on my list.

MB: Yes, they are jewels. I also feel that way about ‘Royal Winter Music’, and I plan to learn it one day. I see it as one of the greatest works for guitar.

DT: I think so. It’s not played so much right now. We are going through a period where that kind of language is not in favor, but I think it may come back. It’s just twenty five years old now, and I’m playing it again and really enjoying it.

MB: I also think that it’s not the kind of thing that everybody can play. Just because one plays the notes and more or less the right rhythm, it does not mean that one plays the piece.

DT: I read the each of these plays five or six times to really understand the characters. The thing about Henze is that he very rarely writes abstract music- it’s about people. And the people that it’s about are usually those whose voices are no as heard, and he’s taking their side. His father was a Nazi soldier, and he writes in his book about hearing his father roaming through the streets, drunk, with Jewish blood on his knife, singing songs about killing Jews that day. Henze was drafted, he was forced to serve, he was in a POW camp in England and got out. Also he was a young gay man, and he had to suppress that. So he moved to Italy in 1951 to get away from all those memories and to have the freedom to be who he was. I think those early experiences affected all his later music.

MB: And now to your latest project, the Kernis concerto. Tell me about that.

DT: First of all, to get any other concerto than the Rodrigo booked is very difficult. Then trying to book a contemporary concerto is even more difficult. So I thought that a new, relatively short contemporary concerto that could be played alongside the Rodrigo might get some play. I approached Aaron with this in the mid 90’s and we mutually came upon the idea of him arranging material he had written before into a new concerto. He took two movements from his piece “100 Greatest Dance Hits”, which is for string quartet and guitar, and then added strings to a movement that he had added to the ‘Partita’ in 1995. I was really satisfied but I thought that a new concerto had to have a cadenza. And so he said to me: “I really don’t have the time, can you write it?” It’s the first thing that I have ever written. It’s about a minute long, but it took a month to write and I could never have done it if he hadn’t held my hand through the whole process. But that was fascinating because I got lessons on the real process from a master composer.

MB: It is curious that although he is such a big name in the American contemporary music scene, he is not all that well known in the guitar world. Of course, that is going to change. But other than you’ I really don’t see anybody else playing his music.

DT: That has been the strange thing to me. Well, you are playing this “100 Greatest Dance Hits” this summer?

MB: Yes, I am.

DT: I really don’t feel greedy about these pieces I get. I want to do the premieres and take them around a little bit and do the first recordings, but I’m not one of these people that want to have rights for 3 or 4 years. “100” is about 7 years old and I have been trying to get other people to play it, and I’m really glad that you are going to do it. I think it’s a real winner of a piece.

MB: I don’t know if I am remembering correctly, but it seems to me that I heard your father say many years ago that commissioning new pieces and working with composers, was a way to make a career…

DT: I didn’t make a plan like that- I just followed my musical instincts.